The More Things Change—a Memoir of the 1940s Still Relevant Today by Theresa Gauthier

They Called Us Enemy by George Takei

George Takei has become a pop culture icon. With more than three million Twitter followers, there are a lot of

people hanging on his every word. It’s his fame and popularity as Lt. Hikaru Sulu on Star Trek that set him on the road to having this much clout, but it’s how he’s used it that keeps those three million people checking in on him.

They Called Us Enemy was released in 2019, this is a memoir that focuses on Takei’s experience in Internment Camps following the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor when the United States of America locked up generations of American Citizens and Japanese immigrants for being Japanese.

To George Takei and his family—an American born mother and a father who’d managed to immigrate from Japan and establish a successful business, but was denied the opportunity to become a citizen—it was a betrayal.

Takei admits in these pages that he was too young to understand a lot of what was happening at first, but it’s perhaps a necessary perspective in telling this history.

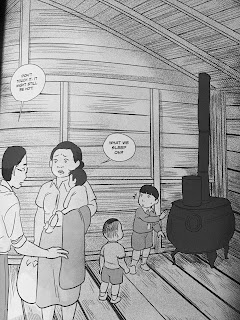

As the reader dives into the story, the art brings it to life. Black and white line drawings are effective in relating this history. Illustrators Justin Eisinger, Steven Scott, and Harmony Becker live up to the daunting task of recreating Takei’s childhood memories. They’ve captured the quiet dignity as well as the occasional anger, fear, and worry of the internees.

with brother Henry, a toddler, and sister Nancy, an infant. His mother works hard to take care of her family, breaking rules when she felt it necessary if it impacted her children’s well-being. Children being resilient, the trio adapted to life in the camps in part because their parents were able to protect them. George’s father, Takehuma Norman Takei took on a leadership role—helping others get settled and managing the day to day lives of the internees.

The innocence of Takei and his siblings as they struggle to make sense of this, as they recognize the unhappiness of their parents, but so little understand exactly what’s happening is poignant. At one point, tricked into taunting a guard by an older boy, Takei’s explanation to his father of what he said to the guard elicits a reaction he didn’t anticipate.

It’s in retrospect, as George Takei grows up that he understands things from his parents’ point of view. His understanding of the toll it took on them to have been ripped from the life they’d built came in gradual increments, but it would have been impossible for it not to come at all.

Being moved from one camp to another, his mother’s irritation at not being able to cook for her family, the risks she takes—on more than one occasion—while trying to do what’s best for her young family, bring home the injustice of these years.

It’s my fervent hope that this graphic novel becomes required reading on school reading lists around the globe.

.jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment